A 2,000-year-old mummy at the Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki

The story of a female mummy from the 4th century AD - with her chestnut braid still intact and a gold-embroidered silk fabric accompanying her on her eternal journey - reveals an exceptionally rare discovery for the Hellenic world.

The word mummy, filled with mysterious and somewhat macabre overtones, is not commonly encountered when speaking of Greek antiquity, more strongly associated with the funerary traditions of ancient Egypt. This is why the female burial now on display at the Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki is such a captivating find, rich in unique details – from the body itself to the luxurious fabric that once enveloped it.

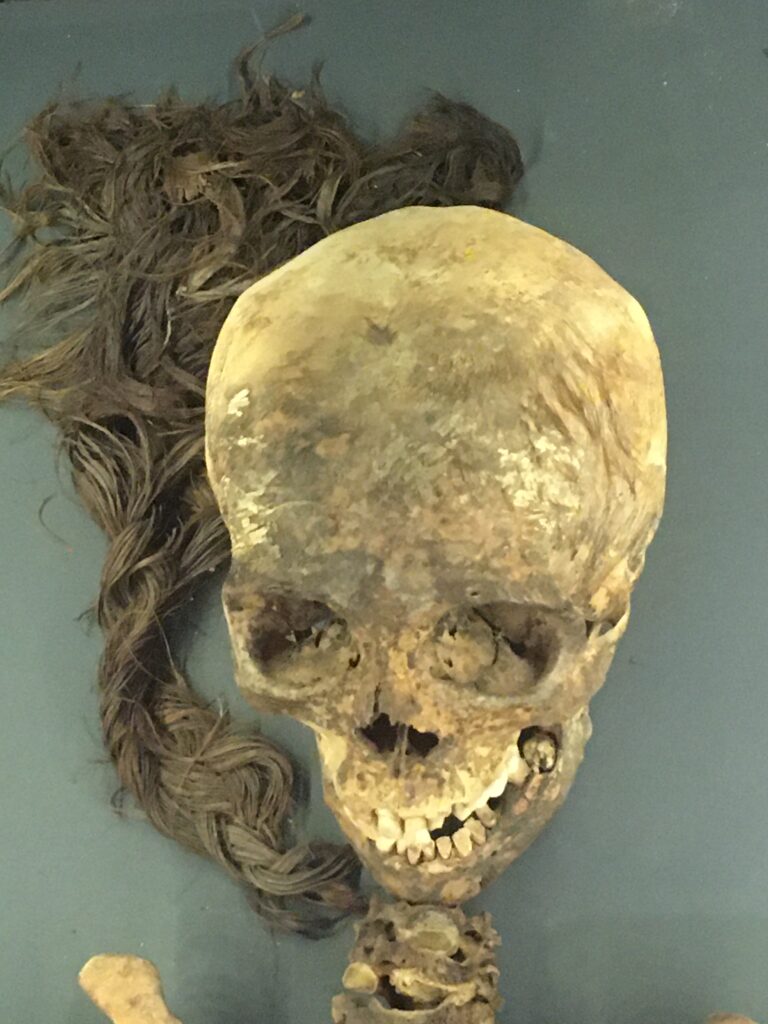

Her story begins on May 15, 1962, when excavations at the eastern cemetery of the ancient city – a burial ground in use from antiquity onwards – brought to light a marble sarcophagus. Inside was a lead coffin, which in turn revealed the well-preserved, partially mummified skeleton of a woman who had lived in Thessaloniki in the 4th century AD.

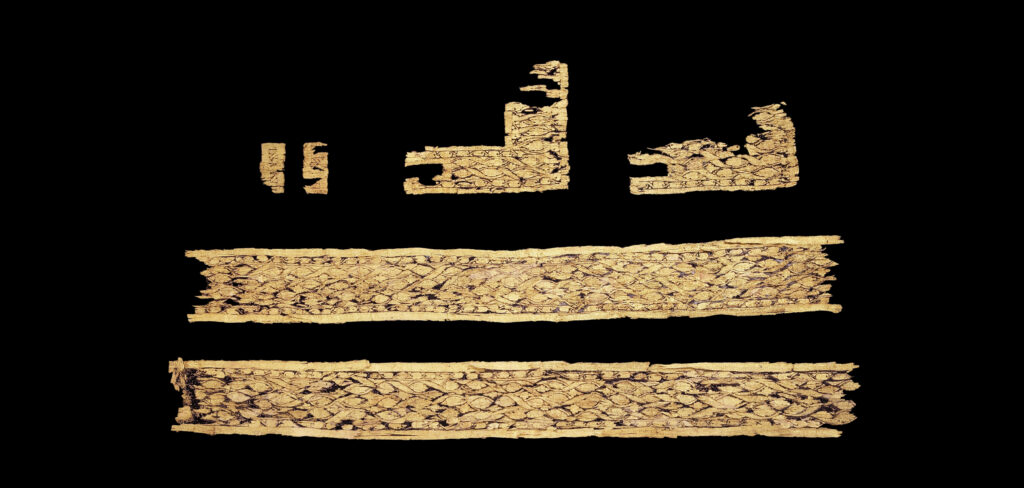

Her body was covered with a purple silk fabric, dyed with a plant-based substitute for precious Tyrian purple and embroidered with golden threads in vegetal motifs, one of the very few ancient textiles preserved in Greece.

It is not only the exceptionally rare embalming technique – at least for this region and historical period – that makes the discovery so fascinating. Thanks to the shrouds soaked in resins and aromatic oils, traces of soft tissue, skin, and muscles were preserved. The archaeologists who opened the coffin were confronted with two astonishing surprises: beside the skull lay the woman’s nearly intact chestnut braid, while even her eyebrows had survived in remarkable condition. Moreover, her body was covered with a purple silk fabric, dyed with a plant-based substitute for precious Tyrian purple and embroidered with golden threads in vegetal motifs, one of the very few ancient textiles preserved in Greece.

But who was this woman, who crossed centuries to share details about her time? The luxurious materials of her burial, the embalming process, and the healthy state of her teeth and skeleton suggest a woman aged 50–60 years, who undoubtedly belonged to a high economic and social class. She had lived a comfortable life, was well nourished, and showed no signs of having endured manual labor.

When you visit the Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki, take a moment to meet her – and let your imagination run wild.

See also

The unparalleled splendor of the Derveni Crater

The undisputed masterpiece of the Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki fully deserves its reputation as one of the most important works of ancient bronze craftsmanship – though nothing compares to the experience of seeing it in person.

The incredible adventures of the Lion of Cythera

The powerful marble archaic lion that dominates the Archaeological Museum of Cythera has endured a true odyssey – changing hands and homes many times over before finally finding a permanent shelter.

The well-guarded secrets of producing an exact museum copy

How are exact copies of emblematic museum exhibits made and what do we need to know about this clandestine process? What separates the good from the bad and what makes an exact copy a stand-alone work of art?